It was Easter Monday in New Jersey, wicked storms pummel the area increasing the likelihood that the power and internet will go out. I’d like to be reading a book with a cup of tea in hand. Instead, I was texting my friend from high school, comparing notes on COVID-19 and trying to guess at what point I call the doctor about my husband. After being in and out of the hospital for the past month, my friend Jane had finally come home recovering from COVID. She told me if my husband’s shortness of breath worsens, it will be on or about day 10 that pneumonia may kick in. Figures; that day will be our 26th wedding anniversary.

Jane is one of my few Facebook friendships. We met in junior high in Oakland, New Jersey. A dozen homes, three states, two countries, and twenty years later, we both landed in the same rural town in Northern, New Jersey. We reconnected at field hockey through our daughters and then again through Facebook.

I didn’t know she was sick until I went on Facebook last week; about the same time I started tracking hospital bed capacity in New Jersey (here for NJ, or here interactive, global data).

Jane doesn’t know I know the data. She doesn’t know I’ve been down this CDC road before when, ironically on my 20th wedding anniversary my husband almost died from a tick bite. Instead of a romantic weekend in Cape May, we spent that weekend in 2004 in and out of the hospital and doctor's office. We later learned it was Erlicha, a bacteria that starts with flu-like symptoms but can cause the body to shut down. My husband is proud to say his case is in the CDC database, one of only about 300 that year. We avoid talking about the specifics of that weekend, other than to say, if we had waited another day or two, or listened to the ER doctor, who advised us to “ride it out,” my husband probably would have been a goner. Regardless, it did compromise his immune system, and he’s now 65, placing him in the higher-risk group for COVID-19.

Why the CDC Lacks the Critical Data

I’ve worked in the data and analytics space for more than 25 years. I worked on the world’s first global data warehouse for Dow Chemical in the 1990s. Since then, I’ve worked with numerous hospital systems across the country, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid, and local physician’s groups on leveraging their data for patient care and staffing. While newspapers such as USA Today and the Wall Street Journal are asking why the CDC has largely been absent from the COVID-19 discussions, the reasons have been painfully clear to me. The CDC does not have the data to respond to COVID-19. The data they do have is too aggregated, anonymized, and outdated to be actionable. This is not the CDC’s fault - they have done the best they can when hindered with strict privacy laws and outdated data systems. I applaud that they are now hiring a Chief Data Officer (CDO), a role that most private sector organizations have and one that the Department of Defense filled several years ago. Unfortunately, for the immediate crisis, the CDC CDO will be too late. Our best hope now is at the local level. Here’s why.

Data Gaps Start at the Doctor’s Office - and at Home

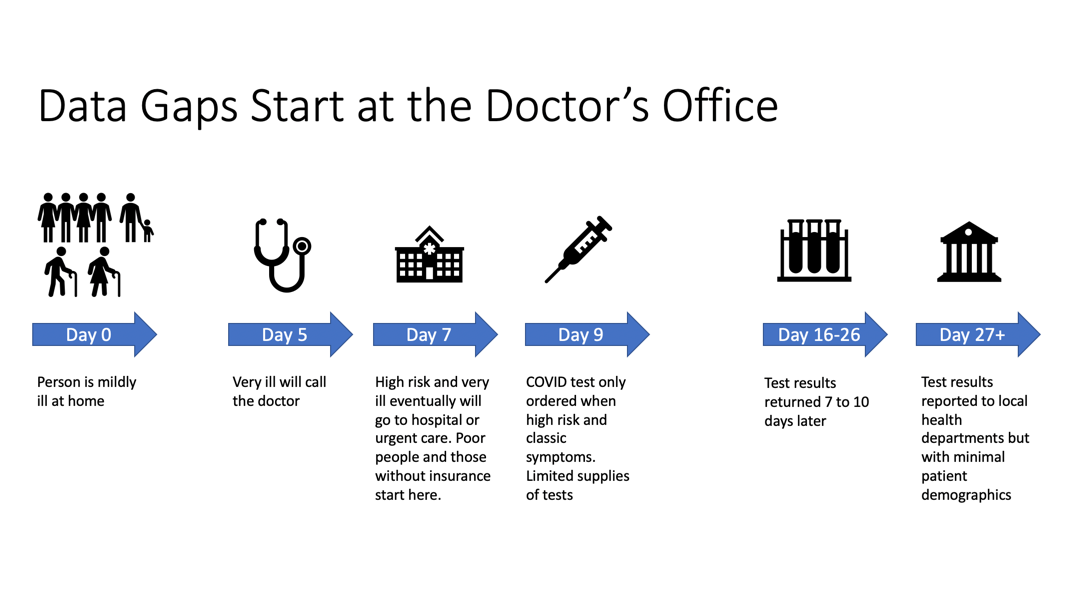

Experts have estimated that 50 to 70 percent of the U.S. population will be carriers of COVID-19. Data from China suggest that children - asymptomatic carriers of COVID - probably accelerated the spread of infection; early data in the U.S. shows a similar pattern, according to an article in The New York Times. In other words, most people with COVID-19 will never go to the doctor to seek treatment. As the CDC just released its first detailed contact tracing report, it may take two to six days after exposure for someone to notice symptoms - all the while, they’re capable of spreading the disease.

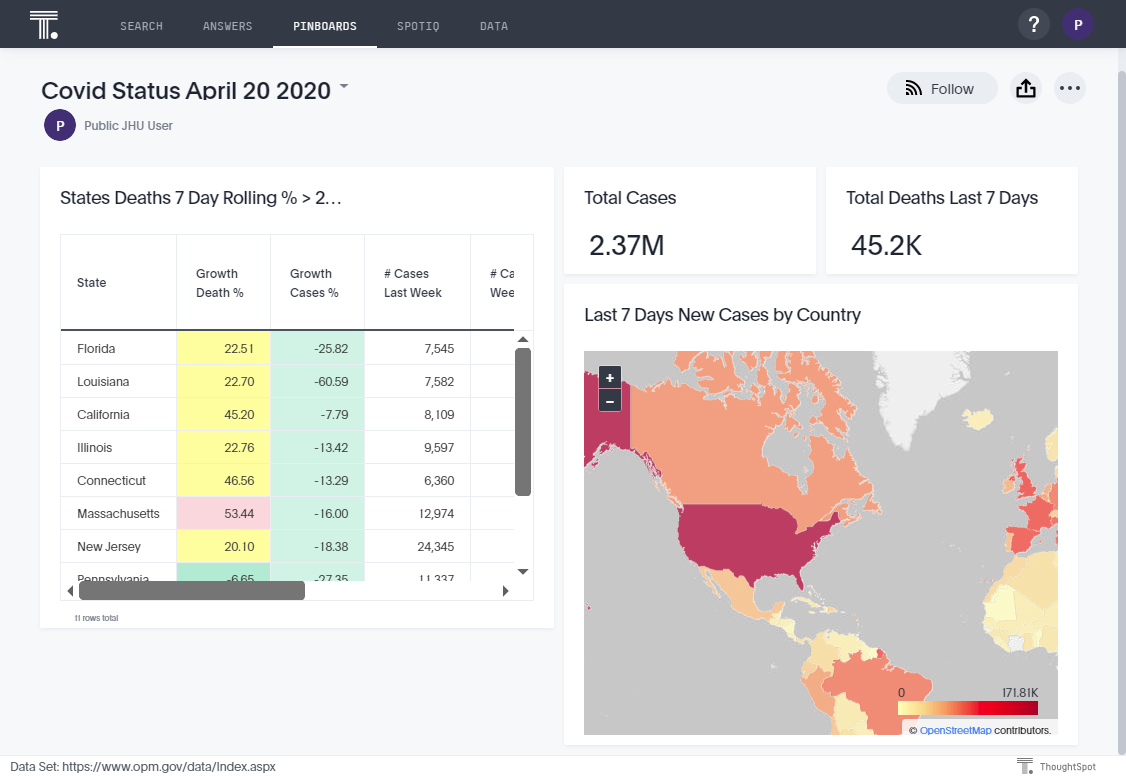

As Figure 1 shows, those who do contact their doctor will not necessarily get tested, because we lack a sufficient number of tests and/or insufficient capacity to analyze the results. The same cannot be said of Taiwan, who learned its lesson during SARS (see Dr. Jason Wang, Stanford Medicine talk, 03312020).

So for now, if a high-risk person shows shortness of breath, muscle aches, and fever, it’s recommended this person be tested but only if in a high-risk group. Drive-by-centers in Bergen County, New Jersey were already running out of tests a few weeks ago, before the death rate climbed. The most severely ill people would go to the hospital. This is where the data gaps begin. In the UK, one reason experts are speculating there is a higher death rate among men; my Yorkshire, England-born husband never goes to the doctor unless he is dire. There are differences in behavior and biology.

Once at the doctor, the data gaps worsen. Just think about how much data you do or don’t give your doctor when you call or visit him or her:

How often do you drink alcohol? (Or let’s phrase it in a way to ensure we never answer accurately: how often do you USE alcohol)

Do you smoke?

Do you have a history of diabetes or Alzheimer’s in your family?

How often do you exercise?

Are you overweight?

How often do you take Motrin or any other over the counter medications?

History of asthma or bronchitis?

Did you get a flu shot? (If you got it at CVS or other drug store, that data is only shared with your doctor when permission explicitly granted)

What race are you (did you leave that blank for fear of discrimination in care?)

Blood type?

Vaccination history (see here for suspected correlation to immunity)

And now the motherload of them all - as you filled in all those complex privacy papers, otherwise known as HIPAA - with whom did you give permission for your doctor to share this data? Whatever data you shared with your primary care doctor will only be shared with that hospital if you granted permission and if the doctor participates in that hospital’s network.

If you are poor or lack a primary care physician, your first entrance may be an urgent care center or hospital where there may not be time to do a full medical history. New Jersey test sites require a doctor’s prescription and will only offer the test to county residents. The people without access to a doctor to write a prescription cannot get these tests at the drive-by centers. Ditto for the out-of-state grandparent.

As I watch the hospital capacity trends for New Jersey, the likelihood we will be seeking care in-state ten days from now is slim. I will take my chances further afield. As long as the borders don’t close, as they have done in Rhode Island, seeking out-of-state care may be a better option by then. Unfortunately, the most medical history those care providers will have on my husband will be from my memory.

Data Latency: From Infection to Confirmed COVID

If there is a reasonable assumption that you have COVID, the hospital will order a test. The time for test results varies across the country and each week, we do get faster at this. But from the time of infection to illness to test results, we are looking at about 26 days. This is one reason why I do not see Contact Tracing as a panacea. It’s one part of managing the pandemic but it’s rather far in the process (and in the future) to be actionable.

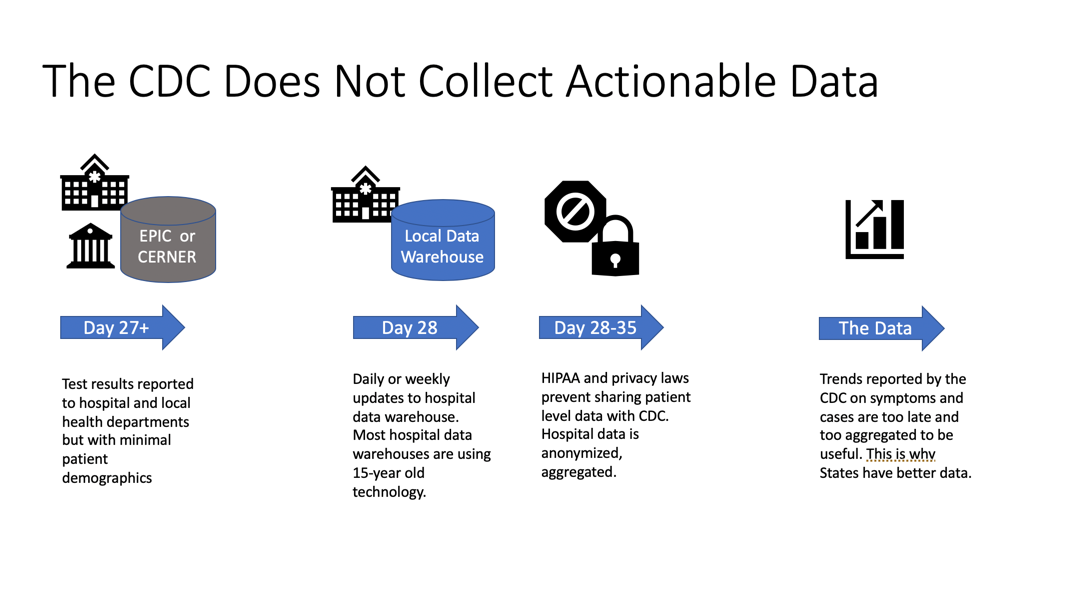

Once you have a confirmed COVID-19 case, the lab and/or hospital reports the incident to the state. This is where the data flows become a mess. The lab does not have much of your patient demographics. The hospital has a little more, but this data is trapped in EPIC or Cerner, the two major hospital records systems. Now, every business person who has relied on SAP ERP or Oracle Financials or NetSuite, knows that these systems are optimized for data capture, not analytics. Furthermore, as Gartner maturity models have consistently shown, healthcare is one of the least mature industries. A lot of smart people in data work in healthcare, but investments in both technology and in upskilling have not been a high priority. In working with a number of these organizations over the years, when I would recommend a state-of-the-art data and analytics architecture it is still considered radical. Often, the decision came down to making do with the lowest cost, which meant using 15-year old technology or perhaps even crunching available data (which may be minimal) in spreadsheets. Gosh, I picture the passionate but dedicated data person in one hospital who had to fund his own education to attend a data and analytics conference. He’s probably pulling all nighters right now, trying to answer so many new questions from everyone from the CDC to the Governor to the citizen ⸺all about a virus we were not tracking until a month ago.

A number of hospitals and emergency room physician groups have built their own data marts and data warehouses; 240 actually share the same data extraction scripts and models from D2I that I’d like to see ramped in the states with the most COVID cases. Currently, these datamarts are updated daily or weekly, fed with a subset of the data that exists in EPIC of Cerner. Daily and even hourly updates are needed in a pandemic, so such update frequency is again a new requirement. A newer healthcare analytics company, Apervita, also has various levels of data from healthcare providers and payers.

With each data load process, data will be aggregated to a degree and anonymized further. To protect our privacy, only highly aggregated anonymized data is sent to the CDC. This means that counts of a flu or virus (or even my husband’s Ehrlichia) by state are reported to the CDC. But granular data of the incidents by gender, age, zip code, race, health background, blood type and more is simply not provided to nor tracked by the CDC. This results in data that is not actionable and explains why we have little idea why some people get more sick than others, beyond age. Collecting more patient demographics is an entirely new data and analytics requirement. It is only this granular data - not the aggregated data- that is actionable in predicting and protecting the most vulnerable in becoming severely ill.

This is one reason that we have limited understanding why more African American’s are dying nationally from this virus compared to Caucasions. Remember - did you answer this data on your doctor’s intake form? Even when you did, it is not shared with the CDC. Only certain counties and states are aggregating COVID cases by race - New York and Louisiana were two of the first, but other states are increasingly reporting this data.

So one of my Easter Sunday phone calls was to my son’s friend, a young man who now allows me to call him Godson. He’s safely away from NJ at a dorm room in California, but his family is from the poorer parts of Englewood, New Jersey. I asked him, how is his family and did he understand what the news was saying about more African Americans contracting this? He is African American. It’s brutal to look at the bias in the data and those who get tests at all. I suspect the reason 78% of the tests are positive in one of the poorer cities in New York (compared to only 46% positive in New Jersey, as of April 13) has more to do with who has health insurance and the means even to get a test before becoming desperately ill. If you are poor and lack a car, you are not going to a drive-by test site; your test most likely will only be when you are so sick that you are finally at the hospital. Tragically, just over half the people tested in NJ are getting tested but perhaps for potentially non-urgent reasons. These may be from mild symptoms that turn out to be a different illness or because they were exposed to COVID-19 but are asymptomatic. It would be ideal if there were enough tests available and results instantaneous, like in Taiwan. But that’s not where we are today.

Whose Data Do You Trust

Is nobody else surprised or concerned that a class project by Johns Hopkins University is now the source of COVID reporting nationally, instead of our federally-funded CDC? The University has all the agility and imagination without the fear of a Senate Judiciary community to pull this off. As the COO of a major insurer said to me back in January (before either of us knew anything about COVID-19), the data and analytics industry does not have a talent gap, we have an imagination gap. I would add, such imagination is further stifled by fear of failure, fear of doing anything differently from how we’ve done them before, and fear that anything less than perfectly clean data should not be used. Oh, and in healthcare, insufficient funding has further hindered efforts to be data driven.

Nobody’s COVID data is perfect. Just last week, I could consult the Sussex County Health department’s website that we had had 41 deaths as of Thursday, April 16, or I could rely on the State’s dashboard that was counting 43. The difference in numbers could be based on who died at home or in a nursing home, a whole other set of data gaps. I would have loved to discuss this with my old professor from Rice University - Professor Williams, who founded one of the largest funeral homes in the USA. He also taught me statistics and entrepreneurship. How ironic that his data is counted last in this whole COVID process. The tragic nursing home news from my rural corner of New Jersey, will be played out in other parts, like it or not, ready or not. The data will come later. Does it soften the blow if I repeat management guru Jim Collin’s advice, only those organizations who can “confront the brutal facts” that data reveals will perform and survive better?

Pretty soon, I suspect the University of Minnesota COVID dashboard may be more widely used because it also contains hospital capacity and ventilators used (ThoughtSpot is loading that data here and we alternate on whose data we really trust - maybe USAfacts is better). I’m grateful to those Minnesota students for manually going to each individual State’s websites, health departments, and obituaries to collect that data.

My big question: what happens at the end of May when these students are done with school?

Even if the data is not perfect, are we glad for the timeliness of the data? I am. I know the limitations. I know the sources.

2020: How Much Worse Can It Get?

I am normally an optimist. But I know the data and I do not like what I’m hearing in terms of the data we are using - and not using - to battle COVID-19. Whether you believe Amit Prakash’s model or these epidemiologists for how many will die and our shut-down patterns, we are in for a difficult year, emotionally and economically. Not six weeks, more like six months at best. I can wish for a cure or a vaccine to arrive sooner, but what I would rather see is a team of data and analytics experts across these various data collection points come together to better share data and to leverage AI. I’d ask ThoughtSpot customer CancerLinQ to share their best practices in bringing patient data together from hundreds of care centers to improve care. With better data, based on those in electronic medical records, we can generate models to predict illness and to share our finite medical supplies. In a state of emergency, sharing of this data across hospitals is newly permissible. With the right data and analytics platforms, data can be used to more precisely inform the public of risk factors. Crowdsourced data collection efforts for people who don’t ever go to a doctor also have a role to play. I’ve also been encouraged to hear how some 911 operators and Mt. Sinai Medical are using symptoms based on calls. There are many compelling initiatives, but they all are siloed approaches. As NJ Governor Murphy said, “the more data, the better.” Sharing of the range of data among medical professionals does not necessarily involve an invasion of privacy. It simply means each siloed view needs to break down their barriers and start talking to one another. It also requires an imagination and understanding of what is even possible with AI and predictive analytics. This crisis reminds me a lot of what happened after 9/11. The difference with 9/11 is that we had the luxury of time and hindsight to figure out how to do better. We need ALL these solutions: predictive analytics on medical data, more lab results, comparison of treatments, antibody testing, allocation of medical supplies and personnel, contact tracing, and a vaccine. None of these approaches alone is a panacea. To hope otherwise is wishful thinking.

As for Jane, she’s planning a COVID recovery party for when she’s fully recovered, and the stay-at-home order is lifted. My husband? He’s more worried about keeping his small staff of manufacturing workers, who live paycheck to paycheck, on the payroll than he is about his health. I look ahead past this anniversary to a day in early summer when we can simply go for a walk on the beach at the Jersey Shore. He still owes me a stroll on the beach for the one we missed on our 20th anniversary.

Thank you to experts who helped review drafts of this article including but not limited to Lindsay Betzendahl, healthcare analytics expert at Health Data Viz, Scott Richards, CEO, d2i, Dr. Jon Ochoa de Eribe, Spanish Centre for Astrobiology (CAB-CSIC and INTA) and Ryan Mattison, ThoughtSpot.

<br>

<br>